“Someone I loved once gave me a box full of darkness. It took me years to understand that this, too, was a gift.” -“The Uses of Sorrow” by Mary Oliver

It was a dreary June evening in Sudbury, Ontario, and I was fresh out of the psych ward, wearing my street clothes and having brushed my hair for the first time in months. I was waiting for a bus in the rain, with one thing on my mind: I was different. And not in a good way.

The alienation and the shame I felt in those days hurt more than Bipolar. Hurt more than my family’s grief-stricken faces upon seeing me and my cut-up neck in the hospital–more than the psychiatrist’s prognosis, more than the dreams I was sure I’d have to forsake.

I was alone. I felt like a freak of nature, with my head now replaced by a giant neon sign that read “Bipolar.” I had spent so much time trying to love and accept myself, and now it seemed I was tasked with the insurmountable quest of loving myself again, only with this diagnosis sitting awkwardly upon my weakened shoulders.

Healing

After much reflection, the only question left was: how do I heal?

It took patience, reflection, forgiveness, compassion, and strength. It took art and exercise and time baking bread and drinking tea with my mother. It took spiritual practices and time. More time than I would have preferred, to be honest, but in the long run, looking back, was it really so bad?

After years of gains and setbacks, defeats and victories, I made a decision. I was going to apply to the West Kootenay Rural Teacher Education Program in Nelson, BC, with the hopes of becoming a classroom teacher.

For twelve years I had been sitting on a Bachelor of Arts in English Rhetoric and Media Studies, doing nothing with it. Waiting tables. Checking groceries. Housekeeping. Answering telephones. Going from one town to another, hoping for change.

My self-image was so outdated; I so desperately wanted to still see myself as that young, bright, capable, witty student who aced her essays and got invited to dinners with local authors, whose professors described as having a “beautiful mind.”

Now, I felt dim-witted and slow. Sick. Vulnerable. At the mercy of my brain. If I wasn’t my mind, then who was I?

When I looked at my experience over the last twelve years, could I really say I was brilliant? Could I really say I was even still capable of writing a literary essay? It seemed like the information would get jumbled and blurred and I wouldn’t know where to start.

For a girl who’d always done very well in school, now I was confronted with the reality that I wasn’t so capable of understanding information, learning, remembering, and making connections.

I wasn’t so inspired or bright, and worst of all, my confidence had suffered a huge blow. Maybe all the ways in which I defined myself in the past weren’t so dependable after all. I knew I had to forge ahead and create a new identity, but starting from ashes felt nearly impossible.

When I was a little girl, I wanted to be a teacher. I loved school and my teachers, and I was often asked to lead groups in activities. I remember once I even wrote, directed, and starred in a school play.

It seemed like the natural progression of things. There are still many teachers who teach from a place of academic privilege, which I think is great for some students, but alienates others.

During my undergraduate degree, I was so focussed on writing, I considered teaching beneath me. I wanted to be a writer. I wanted to teach at the university level.

Afterward, during those twelve years I spent vagabonding and living at the Ashram, I was stuck between these two ideas. However, what I thought I had to offer didn’t hold anymore, as I began to see myself more like a free-spirit who was trying very hard to figure herself out.

The bright academic leader seemed like she belonged in a place lifetimes ago.

After my mental health diagnosis I thought I couldn’t do anything.

Believing In Myself & Others

It was through prayer and chanting, various practices, art and physical exercise, friendship and community, that I began to believe in myself again.

I thought maybe what I had to offer young people was not my natural talents and intelligence–how I began my journey–but perhaps compassion, forgiveness, patience, strength–the very things that helped me heal in the first place.

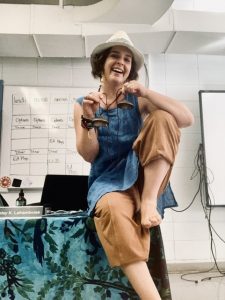

I am now in my fourth year of teaching. I’m by no means yet the teacher I want to be, the teacher I’ll grow into, but I’m learning.

I believe that had I not gone through the challenges I’ve faced I wouldn’t be able to be so understanding to young people–with their emotions and anxieties, their stories and limiting beliefs.

I have felt these things too–and it is through understanding and relating with them that trust is formed, which fosters a safe environment for learning–and, perhaps, more importantly, relationships: a shared humanity that helps young people grow into thinking, feeling adults who care about their own hearts, the land, plants, animals, and others.

I have heard before of the “wounded healer,” where someone’s wound becomes their healing power, and maybe my mental illness, and the qualities it helped bring out in me, is mine.

I don’t think of Bipolar as a curse anymore, so much as a gift–something that allows me to offer compassion and understanding with sensitivity and humility to those around me, and especially to young people who need it the most.

Where Bipolar once alienated me, now it connects me to others. I understand suffering in a way I didn’t before, and from the mud of anguish and fear and loneliness comes the flower of generosity, compassion, wisdom, and joy.

Ashley Laframboise

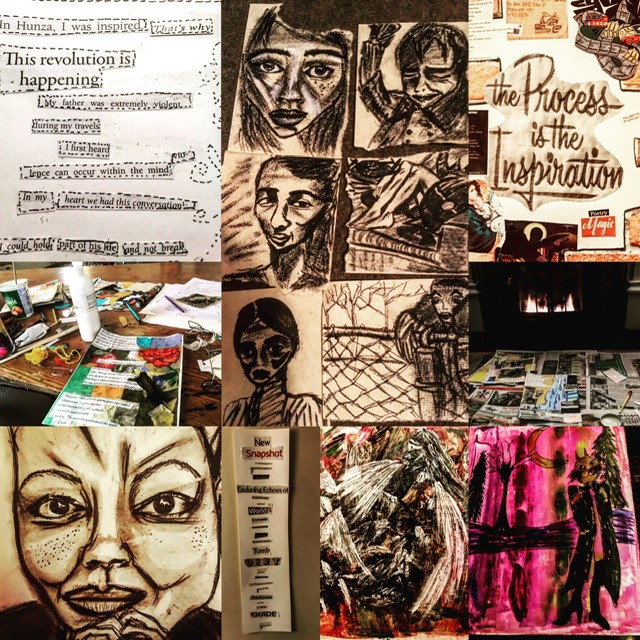

(Original artwork by Ashley)